How Meetic Hires Software Engineers (part 1) : The Design Principles

In my previous post about Meetic's engineering organization, I explained how our matrix organizational structure relies on both the hard and soft skills of our software engineers. We need both to maintain high-quality standards in our tech systems and keep pace with product innovations. This requires engineers to be proficient in writing software and collaborating with product teams.

However, it is one thing to write about the importance of working with skilled professionals, and another to actually find and hire them. Google, Apple, and Facebook all claim to hire the best, and Valve was already doing so in 1996. Similarly, Reed Hastings begins his book about Netflix culture by stating that the content only applies when working with the best.

But what if you're not a Big Tech company? What if you cannot afford to pay everyone in the 90th percentile of San Francisco market rates, regardless of their role or location? In the last decade, there has been inflation in engineers’ salaries in France and elsewhere, making it difficult to attract the best talent even if things stabilize.

Although Meetic does not face the same engineering challenges as Google, Netflix, or Apple, we are still a social network with millions of active users in Europe. Running and improving the platform requires a certain level of skill. In addition, our organization values the soft skills of our engineers.

In the past few years, I have spent time working on the topic of hiring, first as a backend tech lead, then as an engineering manager, and now as an engineering director. Despite not being Google and not likely to hire the best among the best, I've wondered about what constitutes a good hiring process. How can hard skills be evaluated consistently with the job to be done? How can engineers be attracted and evaluated in the same hiring process?

While testing new hiring processes, I have structured the way Meetic hires engineers. Nowadays, all engineers in my team (and most teams) are hired through the same process. In the following paragraphs, I will provide an in-depth overview of this process. The goal is to share the results of four to five years of work with tech leaders who have the same question in mind. Additionally, I hope this post will be helpful for applicants to understand what we expect and to prepare for our interviews.

Hiring processes are well-known in big tech companies. However, I have found very few details about how companies like Meetic (~300 people, not growing as fast as before, tech-first, etc.) hire.

Meetic's Design Principles for Hiring Engineers

First and foremost, it's important to consider that hiring an engineer can be a significant expense. You must take into account the cost of the search process, which depends on whether you employ your own headhunter or hire a contractor to do the search. In addition, there is the cost of the hiring process itself - every hour you spend hiring someone is an hour you're not working on something else that generates value. The more people involved in the process, the higher the cost to the company. Finally, if you're hiring to replace a departing engineer, there's a good chance that the newly hired engineer's compensation will be higher than the previous engineer's.

This is why it's important to establish design principles for the hiring process, and to define a process that aligns with your expectations for the new hire.

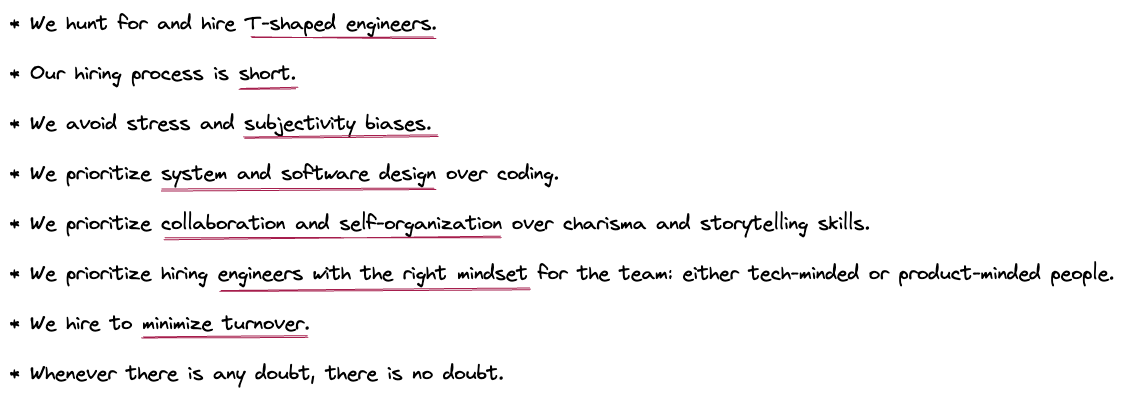

At Meetic, we keep in mind the following principles.

We hunt for and hire T-shaped engineers. These are engineers who are experts in their domain but are also skilled in communication, collaboration, and self-organization. This is important because while our technology requires heavy skills to run, our product teams (or squads) are cross-functional. This means that each engineer works alone on their respective platform (iOS, Android, web, backend, etc.). Collaboration between individuals who don't necessarily share the same skills is challenging.

Our hiring process is short. Unlike larger companies such as Google or Facebook, we are aware that the market is competitive and talented engineers receive many offers. Therefore, we cannot afford to conduct five or more interviews. Time is against us, and a shorter hiring process is also more cost-effective. This is yet another reason why we prioritize a short hiring process.

We avoid biases. Biases can come in two forms during the hiring process: stress and subjectivity. Stress can affect the interviewee's ability to showcase their competencies. To avoid this, we conduct interviews as a conversation. We share information about our work and lead the interview in an open-minded way. When asking applicants to share their previous work experiences, we don't expect them to give the “right” answer. We recognize that what works for us may not work elsewhere.

Subjectivity can come from the interviewers themselves. To avoid this, we have the same interview process for every engineer we hire. They all undergo the same interviews, with the same types of interviewers, doing the same tests and answering the same questions. We use a guideline to evaluate both hard and soft skills, and this guideline applies to everyone we interview.

We prioritize system and software design over coding. We don't rely on platforms like Codingame that emphasize coding skills and knowledge of a particular language. Knowing a language or framework is not the main goal, as technologies and systems evolve rapidly. We don't seek engineers certified in the use of any framework, but rather people who enjoy learning. Furthermore, we don't want people to write clever code; we want people to write code that's easy to read. “Readable” means that I know what kind of work this code is doing (UI, network calls, DB query, etc.) and that I can easily understand what it does, even if I'm not familiar with the language. This is why we prioritize system and software design. Good design goes a long way in understanding what a piece of software does.

We prioritize collaboration and self-organization over charisma and storytelling skills. Not all engineers fit the “nerd” stereotype. Some are very charismatic and excel at public speaking, which is great for our industry. However, these traits are not what we look for when hiring engineers. For us, collaboration and self-organization are much more important due to the way our team operates. Of course, collaboration requires good communication skills, as well as kindness and helpfulness towards others. Sometimes, communication and storytelling may seem similar, but we strive not to be swayed by individuals who excel at telling stories during interviews.

We prioritize hiring engineers with the right mindset for the team: either tech-minded or product-minded people. Depending on the state of the team and the community, we look for engineers with either a focus on technology or on product development. Tech-minded engineers see the code and its architecture as a finality, while product-minded engineers see the code as a means to build products and bring value to end-users. Both mindsets are necessary to build great teams and great products, so we strive to have a mix of both in our teams and communities.

We hire to minimize turnover. According to The Team Topologies book, teams should be considered as a whole, unbreakable piece when thinking about engineering organizations. The more a team works together, the more efficient it becomes. Therefore, when an engineer leaves a team, the entire team tends to become less efficient, at least for some time. Onboarding a new engineer takes time, and getting back to cruising speed takes even longer. This is why, when hiring, we seek to minimize future turnover. There are two things we need to do to achieve this:

- We need to avoid mistakes and hire the right people. We shouldn’t rely on a probationary period to decide if they fit or not.

- We want the applicant to have a clear understanding of how we work, what their day-to-day job will be, and what our management culture is like. Neither the engineering manager nor the applicant should be surprised with the job after the hiring process.

Sometimes, things go wrong, but it should never be because of a lack of information and understanding during the hiring process. Avoiding turnover may sound obvious, but it is not easy. When you take it deeply into consideration in your hiring process, it affects the way you evaluate if an applicant is a good fit or not. It forces you to consider the applicant's future evolution in their role, and it drives you to answer questions like: Will I be able to offer evolutions to this engineer? What will I offer to keep them in the long run? What kind of challenges?

Whenever there is any doubt, there is no doubt. This quote is from a popular French movie (source). It means that if anyone involved in the hiring process has doubts, we will not make an offer to the applicant. Everyone must be aligned, and the decision must be a strong “yes” or a definitive “no.”

The Skills We Value and Look for in Our Engineers

Given the challenges our engineers work on and the teams they are part of, we need a clear understanding of applicants’ skills. In the second part of this post, I'll explain how we evaluate these skills. But first, let's take a look at the skills required to work at Meetic as a software engineer.

In the past few years, we've created a competencies matrix that lists the skills engineers need. This type of matrix is usually designed to help people grow and be promoted, but we also find it very useful as an evaluation tool during the interview process.

We use it as a checklist throughout the interviews.

Of course, it is impossible to both test every competency and keep the hiring process short. That's why we only effectively test some competencies through a dedicated test. Others are evaluated more informally during the interview. The following describes how we evaluate applicants and the types of questions we ask to better understand their skills.

Technical skills

We do not test coding, debugging, or observability skills. Instead, we seek to understand how applicants have handled situations that require such skills. For instance:

- What logging tool did you use? Are you familiar with ELK, Sentry, or Crashlytics?

- Have you ever encountered code where variables were not named according to the usual naming conventions for product teams?

- How did this affect your ability to understand the code?

We consider these skills to be mandatory, as most of the engineers we hire have several years of professional experience, and these skills are typically acquired early in a software engineering career. Applicants either have these skills or they do not. If they do not, we are unlikely to hire them.

However, we do test System Design and Software Architecture skills. In this area, we want to see how applicants apply design patterns in a particular context. There is no one-size-fits-all solution in the software architecture domain; it all depends on the context and the anticipated future evolution. Thus, we dedicate a part of the recruitment process to challenging these skills and seeing how engineers adapt their views to the context.

Delivery

Delivery is all about being accountable, self-organized, and focused on end-user value. To assess the applicant experience with this, we have a few questions:

- Who was responsible for breaking down epics into user stories or technical tasks in your previous job?

- Are you familiar with the Lean culture? How did your previous team deliver value incrementally?

- Have you ever been in a situation where your estimation was incorrect, and you were about to miss the deadline? What was your reaction, and how did you mitigate the risk?

We also ask questions about technical scoping:

- Who was in charge of choosing the right technical solution to build a feature in your previous job? If it wasn't you, did you ever challenge the technical strategy? Have you ever done technical scoping yourself, and how did you work with other engineers in that case? Were they receptive to your point of view on the right technical solution to build?

Collaboration

This area of competency focuses on the applicant's ability to work with other engineers and product managers. We seek to gain a deep understanding of how the applicant worked in their previous team by asking the following questions:

- How was your team composed? Did you work with a Product Manager?

- Did you work alone on your platform, or did you engage in peer and mob programming? If you did, have you ever had a conflict about the right way to do things? If so, how did you handle that?

- How did you shape features in your previous job? Was it something done by the product manager/designer, or were you involved in the process?

- Regarding team retrospectives, have you ever faced criticism in public? How did you react?

- Are you familiar with the 4 A rule of feedback?

Leadership

Leadership skills are not expected from all engineers, but a senior software engineer is a role model. Rather than guiding senior engineers, people look to them for guidance. In his famous book, High Output Management, Andrew Grove calls this form of leadership “know-how managers”: people who have an impact by influencing others, not through a direct report, but thanks to their expertise.

So, depending on the level of seniority we seek to hire, we may ask questions such as:

- How do you strive to be objective and reflect on your own biases when making decisions?

- How do you drive alignment in your team or community? Have you set goals for your team or community before? If so, how did you do it? Did your team reach the goals?

- What does taking ownership of your decisions mean to you?

- Have you mentored teammates before? If so, how did you do it?

Strategic Impact

Like leadership, the ability to have a strategic impact is not something we expect from all engineers. But tech leaders are expected to set up a technical strategy in their community that is aligned with the overall organization's strategy, share the organization's strategy, explain how their technical strategy is aligned with it, and bring technical insights into the process of shaping features. Although not expected from all engineers, strategic impact is essential at some point, and engineers are expected to contribute to the company's success by bringing their expertise to the table.

The ability to have a strategic impact is something we evaluate later in the interview process by reviewing the applicant's past experiences and challenges. We ask questions such as:

- What kind of initiatives have you taken recently?

- How did they go? Were you able to convince your managers and teammates? How did you share your vision?

- Can you describe a situation where you had an impact on your team or organization's work?

Although we evaluate a list of skills during the interview process, we do not use a formal scale or evaluation sheet for each skill. While I have tried using evaluation sheets in the past, I found them to be more useful when comparing applicants to decide who to hire. In our case, we often have a strong yes or no for each applicant, and cannot wait for other applicants to complete the interview process for comparison.

However, we do use the design principles described above as guidelines throughout the interview process. We keep these principles in mind and prepare a list of questions that align with them.

In the next post, I will delve deeper into our interview process. I hope that sharing these details will inspire other hiring managers and help applicants better understand what to expect.