How Meetic works: an organization designed to ship fast and maintain quality

Meetic, like most tech-first companies, needs to keep its code base clean and scalable. It is our biggest asset, and we need to take care of it. Most companies are either good at shipping fast or maintaining high code quality. Doing both is hard and we've been working on this topic for a while.

While there is still room for improvement, I considered we have found the right balance between long-term tech projects and product development. I'd like to share the receipt. Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to organizations, roles, and processes. However, the organization I describe below and the design principles on which it relies are pretty common. Especially for companies that work with both web apps and native apps.

In this post, I'll deep dive into 3 key factors that have helped us achieve great product development success and high-quality standards :

- The way we run our teams and our tech communities

- The hard skills we expect from the Engineering Managers and the role the Tech Leads play in the tech communities

- The hard and soft skills we expect from the Software Engineers

Running both product teams and tech communities

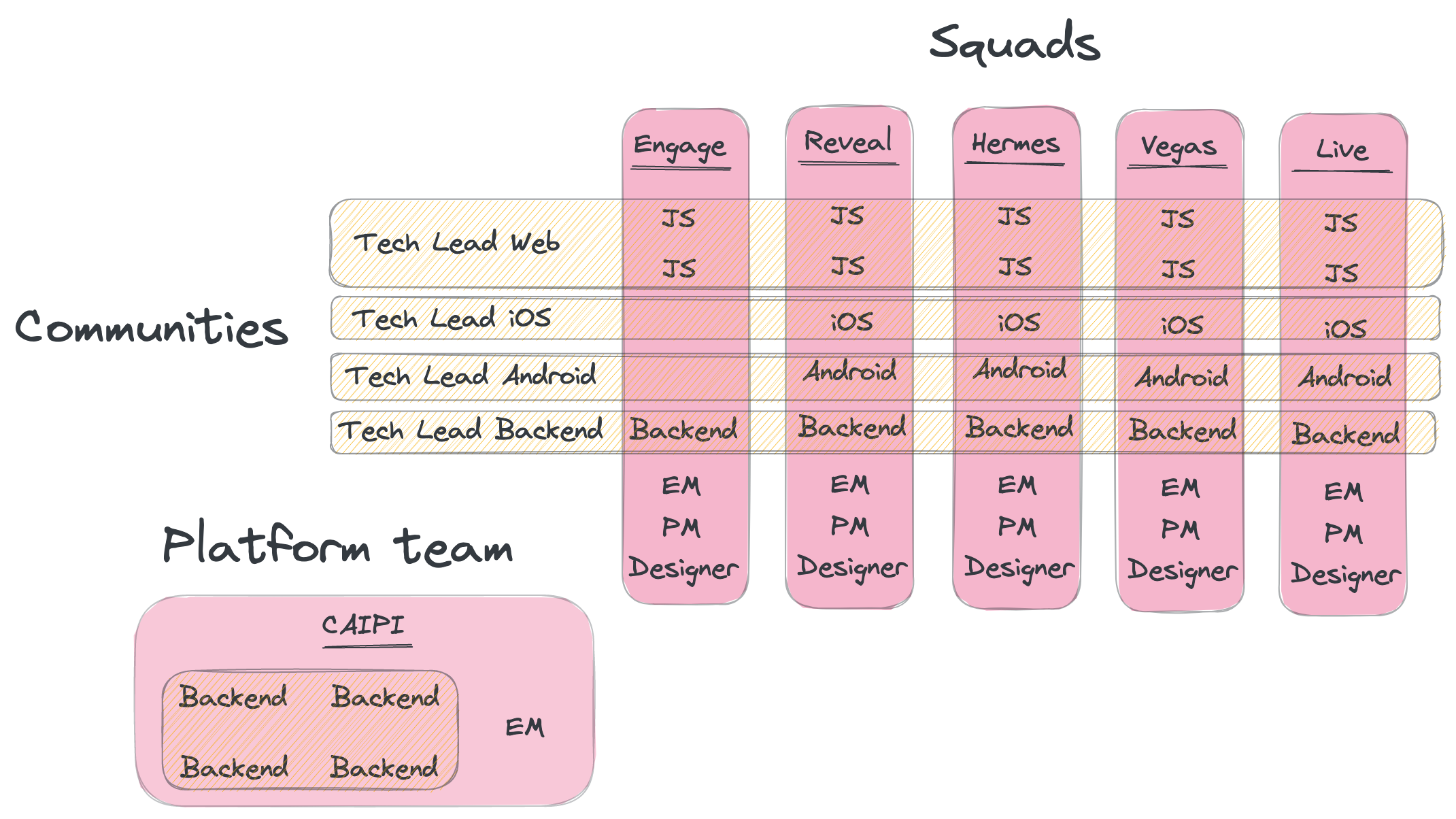

At Meetic, tech communities are groups of engineers sharing the same technical competencies. Most of the time, they work on the same part of the infrastructure. Thus, we have a JavaScript community, as well as an Android one or a Backend one.

Product teams, called squads, are cross-functional teams focused on delivering the best user experience.

The Squads build the product

Each team is really like a start-up. It has a mission - a goal or a KPI to reach - and is composed of all the skills needed to build the best product: some software engineers, a product manager, a product designer, and an engineering manager.

At Meetic, product and tech leaders strongly believe in collaboration when it comes to both product thinking and development. We think that everyone’s skills are necessary to think and build features the lean way. In the process, Product Managers bring their business expertise. Designers help build the best UX. And engineers challenge the PMs and Designers’ ideas to make it cheap to build. The goal is to create the simplest user flow that brings value. This mindset we expect from the teams helps us learn more about the usage and the potential.

Thus, teams work on 3 types of projects.

Quick experiments, which are a form of prototypes. These are what Marty Cagan calls prototypes with live data. Quick experiments typically take a few days to build. No more.

Feature versions. When building a feature, we have a goal in mind. But there mostly are plenty of ways to reach the goal. This is why we almost always start by building an MVP of the feature. Then we ship it and see if yes or no, we get closer to our goal. Then, we start iterating on the feature. We ask the teams that each iteration, including the MVP, takes less than 6 weeks to build.

Small changes, which are the kind of evolutions we do either by convictions or other teams’ requirements. It could be the marketing team, the legal & privacy teams, the security team, etc.

From a technical point of view, quick experiments are generally considered disposable. In this area of work, we assume doing quick and dirty stuff. But only because we know that, if an experiment leads to identifying a good opportunity, we will build the feature from scratch anyway. All other project types are expected to be built on high-quality standards.

The communities keep the code clean

However, with time comes technical debt. And it's ok. Whatever quality standards you rely on, they are likely to evolve. At some point, the code you wrote 2 years ago won't match your current quality standards and best practices. Tech debt doesn’t necessarily come from wrong practices or quick and dirty developments. Practices and languages evolve. We call it technical debt as if it was something you can pay one shot and go away. But, to me, the technical debt is more like a rent you need to pay periodically.

This is why we have tech communities.

The communities goals are to make people share their practices, their ideas, and their readings but also to work on technical projects, mostly refactoring. Communities are accountable for the quality of the code base they own. They are expected to challenge the guidelines and practices, but also to bring new ideas to the table as well as adopt new technologies.

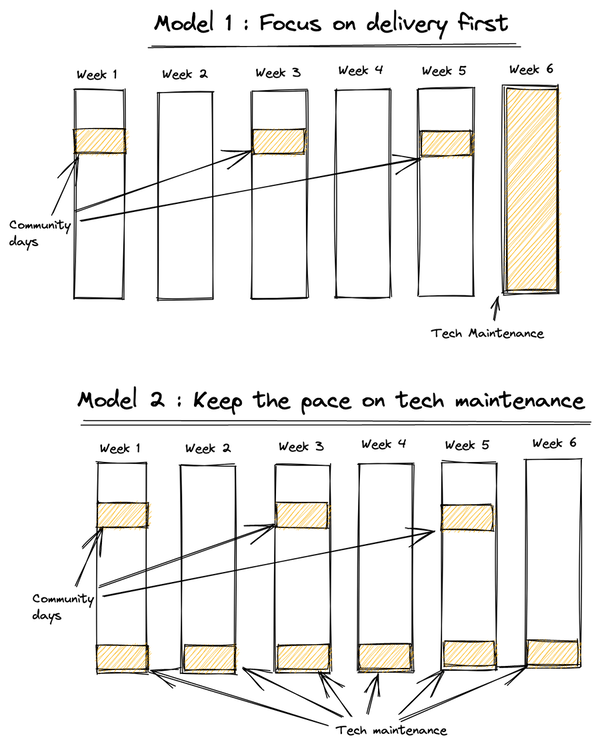

To guarantee the best collaboration on tech topics, we organize what we call Community Days every two weeks (every sprint). These are full days where engineers take time to share and work together on technical topics. The tech leads are expected to set the pace of the day with sharing sessions, workshops, and hands-on dedicated time over the day.

Community Days are important in that they are a convergence point in the best practices design. When the objective and the strategy to reach it are clear, it may also serve as a dedicated time to focus on technical work. But this is not the primary goal. Most of the time, these days are used to scope technical projects and refactoring. Once the community is aligned on what needs to be done, how it will be done, and who is going to work on what, engineers are expected to actually work on technical projects during the sprints.

We try to spend about 30% of our time working on tech quality, as a general rule. Inside the squads, each engineer may act differently to reach this objective. Typically, 30% could mean 1 Community Day per sprint and every Friday. 30% could also mean a full week, after the launch of a feature. It really depends on the context and we try not to be too strict on the way this time is spent.

The way we balance feature development and technical maintenance relies heavily on trust and high collaboration between product and tech. It also requires the Engineering Managers and Tech Leads to be good at scoping projects and helping the teams reach their objectives either business or technical.

To be honest, switching between building features and making small technical improvements is hard. Especially for engineers. It relies heavily on the boy scout rule. But moreover, it requires rigor.

Engineering Managers & Teach leads: key roles in the delivery process

The Engineering Manager role at Meetic is one of the things I've been working on the most lately. This role, particularly, varies a lot from one company to another. At Facebook, EMs may work with up to 50 engineers across several teams. In some others, EMs manage a tech community like frontend engineers. My point of view is a combination of things I've seen in several companies. In its book Turn The Ship Around, L. David Marquet describes what he called “chief in charge”. That is to say, chiefs are really in charge of running the ship. Not higher grades. This point of view is what I found to be the closest to my own. But it sets the bar quite high for managers. Especially because they are expected to own a wide range of things: from software architecture to project delivery.

The managers are hands-on

At least, they should be able to code. And for sure, they have a heavy background in software development. On that topic, Basecamp has a very strong opinion.

Engineering Managers in my team are also Tech Leads or former Tech Leads. This is something I strongly believe in. To me, Managers should know what their direct reports are talking about. Sure, being the iOS Tech Lead doesn't always help you to get a deep understanding of a JavaScript stack issue. But at least, you'll be able to understand the concepts and surely, share some common patterns such as decoupling or testing.

Sharing a common language helps make helpful feedback. Helping people grow both their hard skills and their soft skills is also a lot easier when you share the same experience.

However, there is a limit to being hands-on, as a manager. Coding with the team is considered to be an anti-pattern and I mostly agree with that. This is why Tech Leads in my team aren't expected to work on features. This is something we will see later.

The managers are the delivery key drivers

Not the PO / PM. Not the Scrum Master. The Manager. By key drive I mean: the one that is accountable for the delivery.

Delivery includes the technical scoping, the project scoping to achieve incremental value delivery, the delivery pace (known as the lead time), and the quality of what is delivered in production.

Managers are expected to lead those areas of work. And when something goes wrong in a project, they are expected to either take action or raise a red flag and escalate any blockers.

Being a key driver of the delivery also means driving empowerment. Managers are responsible for making their teams grow. For example, they ensure the teams commit to a realistic amount of work on each sprint. But in the end, the teams commit, not the managers.

The managers sponsor the long-term tech strategy and pay the debt

The Engineering Manager helps technically scope new projects/features. He also recalls to the PM what needs to be done in terms of refactoring and cleaning. This is important to guarantee our long-term capacity to make the product evolve.

When it comes to delivery, it's easy to get excited about the next feature and push the team to go as fast as possible. As I wrote previously, it's ok, depending on the kind of project. But somehow, the time comes when refactoring and cleaning are necessary.

There are many ways to work on technical debt. Some teams work on technical issues or projects every Friday. Others start a “technical sprint” after having delivered a big project. It's up to the manager to decide how the team will contribute to paying the debt. But in the end, the Engineering Managers are accountable for the progress of technical projects in their team.

This mission is surely the most difficult one, in the Engineering Manager role. It is hard to stay focused on business goals AND technical quality. It requires Managers to be very aware of the organization's engineering strategy and sponsor it in the team. Especially when expectations on the business side are high. But once again, it helps to have Managers that are also hands-on.

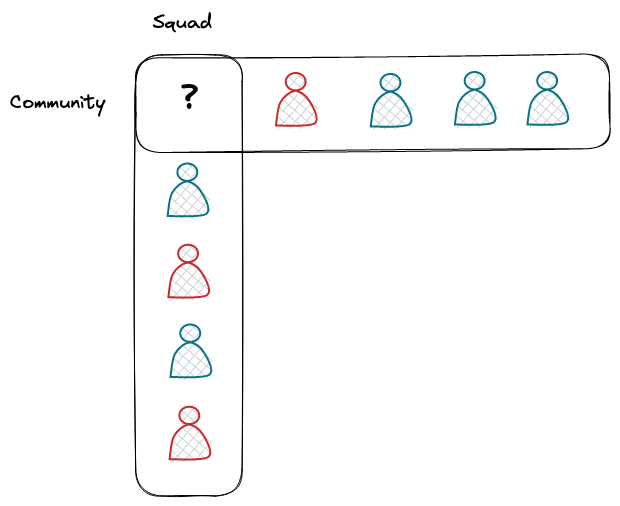

The Tech Leads are project owners and mentors

While the managers work with the squads, the Tech Leads work with the communities. Managers are often also Tech Leads. But all Tech Leads aren't managers. Technical Leadership is a career path as well.

Tech Leads in my team aren't part of a squad. They are either managers or outside of the teams. They are owners of the code base and are accountable for its maintainability and its quality.

Tech leads have 3 missions.

They help define the engineering strategy on their platform. It is up to the Tech Lead to challenge the maturity of a new technology. They evaluate the value it could bring to us. They also decide what kind of refactoring should be done.

They scope technical projects, aligned with the organization's strategy. Scoping is a way to transform strategy into execution. The expected outputs of a scoping are technical tasks small enough to be done in 2 days or less. This is a very important part of their job as small technical tasks are easy to log in a squad's backlog, with the support of the Engineering Manager.

They mentor other engineers. On a day-to-day basis, they help engineers to deliver features. Either by doing reviews and suggesting improvements or by bringing their knowledge when an engineer is stuck.

Engineers are problem solvers, not software builders

In this way of working, engineers are involved in almost every area of work. In my opinion, this is key to empowerment. But to be honest, there are also downsides. Especially, years over years, I came to the conclusion that involving engineers soon in product thinking works better when people have the right mindset and enough seniority.

To give you a better idea of what we expect from engineers, here is a brief description of when they are involved and for what kind of work.

First, during the product thinking and project scoping. They jump pretty soon into the conversation. At this step, their role is to evaluate the complexity and make suggestions to keep things simple enough. Most features are designed collaboratively. Sure, the Product Manager and the Designer come up with an idea, a user flow they have worked on. But the final design will be a trade-off to find the quickest way to offer end-user value. All that collaborative work requires good communication and feedback skills.

Then, during the project scoping engineers also anticipate technical choices according to feature design. They help their product counterpart to identify edge cases. Often, engineers have a deep understanding of the product. After all, they've built it and they can check the best source of truth (the code) easily. This is also during project scoping that decisions are made about software architecture. Scoping is indeed a good time to challenge both the design and the code. If there are things to change in the software architecture and refactoring to do, this is where we decide to either do the change or postpone it until the next big change. The key is finding the right balance. This is why collaboration and diversity of mindset among engineers are such important topics.

Finally, when building, engineers break down the work and anticipate dependencies. They then commit to a realistic amount of work accordingly to priority and urgency. They drive their task across the reviews to minimize the lead time and when something goes wrong, they escalate blockers and delays to their team and manager. To summarize, engineers are expected to fully own their development work. It may sound obvious when talking about software engineers. But yet, this is not. It requires skills that are not only hard. It requires a good aptitude to collaborate, communicate and self-organization.

In recent years, engineers’ missions and expectations have changed a lot. We're coming from a world where tech people weren't involved in almost any thinking about the product. The teams’ missions were to build the product, mostly. But my conviction is that you don't build great products without engineers.

Software engineers are problem solvers, not software builders. Building good software is key, but it's only a small part of the job. I describe the role of engineers as the last piece of our organization. However, from a historical point of view, this is all but true. In fact, the way we build our product while maintaining high standards has mostly emerged after having rethought the way we hire.

Hiring T-shaped people: tech-minded and product-minded engineers

A few years ago, I started to structure the hiring process around identifying T-shaped people in software development. The idea was to hire engineers good at software and system design instead of being just good at coding. I also wanted to challenge their collaboration and communication skills. I wanted to hire software engineers, not programmers. Software engineering is what happens to programming when you add time and other programmers. It requires more skills than just coding.

At the time, I was Backend Engineering Manager. So, I started with my own team and designed an interview process in 3 steps :

- HR screen call to confirm basic skills, previous experience, and compensation expectations.

- A Software Design / System Design interview: candidates had to design a feature in terms of class, http calls, etc. The main goal was to see what kind of software engineering principles (like design principles) the candidate knew and was able to apply to a concrete use case. On a whiteboard, the candidate had to both draw the system AND explain what she does.

- A leadership interview, mostly designed to validate how the candidate could join the community, what kind of skillset she will bring to the table and if their value fits the overall company values.

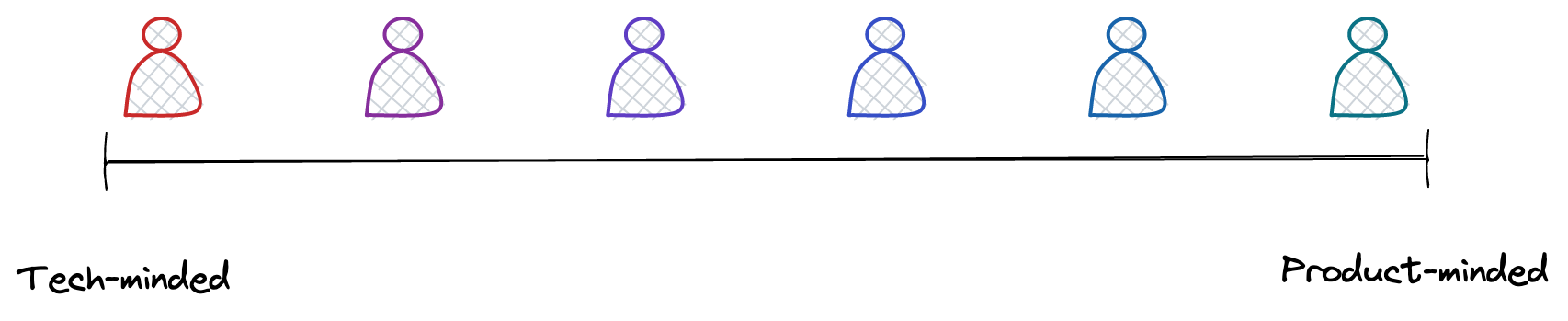

I later rolled out this interview process on all software development roles. It helped me a lot in identifying people able to both build great software and collaborate at different levels. Also, now that I mostly conduct leadership interviews, I focus on finding out if the candidate is either tech-minded or product-minded.

Indeed, to me, most engineers can be placed on a spectrum that ends are tech-minded and product-minded people.

Tech-minded engineers see the code and its architecture as a finality. In their mind, their role is to produce the best software in terms of design principles, architecture, code quality, etc. They heavily focus on those topics on a day-to-day basis. Tech-minded people are often the ones that do more code reviews, like to get involved in every tech discussion, read a lot about tech and share their reading with their community and tend to push tech projects and refactoring in the roadmap. They have strong opinions on what quality means in terms of code and they want things to be done right.

Product-minded engineers, on the contrary, see the code as a means to build products and bring end-users value. They strongly focus on user flow, design and business value. They actively share their opinions when they shape features with their teams. Most of the time, they also defend their core value (typically, they will tend to push back dark patterns in the UX). However, product-minded people aren't necessarily the kind of engineers that produce low-quality code that is not maintainable in the long run. Being product-minded says nothing of their software development knowledge and skills. Most of the time, they know how to write high-quality code. But they often are followers on those topics, not leaders. They learn best practices from tech-minded engineers and then apply what they learned.

As Google has shown in its Aristotle project, diversity of ideas and opinions is key to psychological safety and thus, successful teams. This is why it is important to identify the type of engineer I'm hiring. In the end, the goal is to build teams and communities that are diverse enough to ensure good collaboration on both product and tech. Will it be someone that will raise the bar in its community? Will it be someone that will help the Product Manager and the Designer to shape the best features? Those are the question I try to answer when interviewing candidates.

Thus, each new hiring must meet the following requirements :

- Has a good understanding of design principles such as decoupling and testing and is good enough in system design.

- Depending on the state of the squad AND the community, is senior enough. (if the team and the community already count a large part of senior engineers, it's off to hire people with less experience)

- Depending on the state of the squad AND the community, is tech or product minded.

With that in mind, we conscientiously hire people that fit in the global organization and the outcome we expect from it: ship fast AND maintain high code quality.